PRESSURE

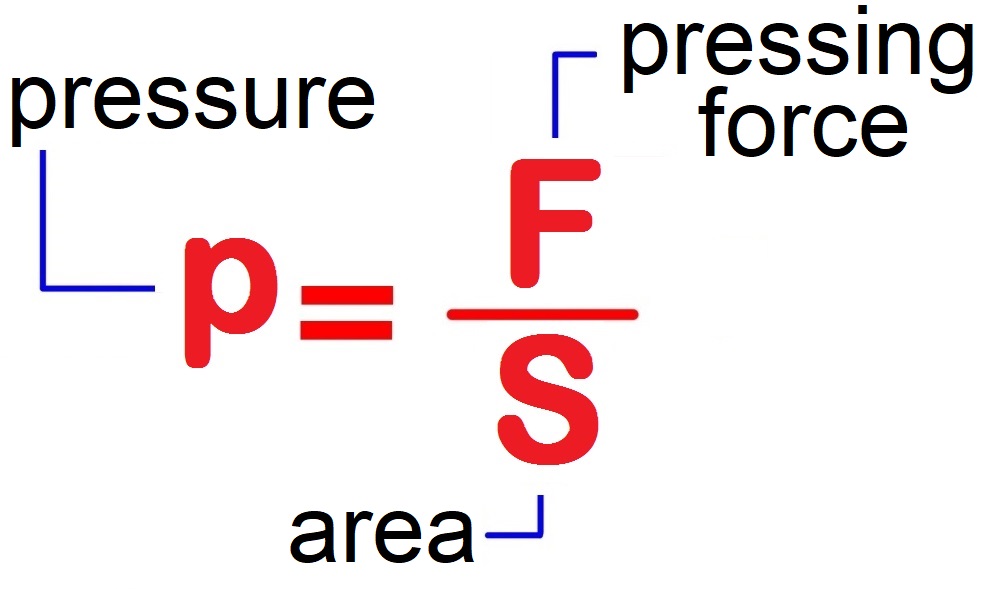

The expressions 'pressing force' and 'pressure' are not synonyms, but are used for different physical phenomena. Pressing force is measured in newtons [N], and pressure is the quotient of the force and the surface on which that force acts and is measured in pascals [Pa]. If we take a brick weighing mg , we can lay it like a block on a soft surface (e.g. sand, dough, plasticine) in three ways. The pressing force in all three cases will be the same mg. However, the footprint that the brick will leave on the substrate will be of different depths.

It is immediately seen that the depth of penetration is inversely proportional to the surface S , the smaller the surface, the higher the pressure.

The difference between pressing force and pressure can easily be demonstrated by an experiment in which we hold a nail between the index finger and the thumb. The tip of the nail has a very small surface compared to the surface of the nail head. The pressing force on both sides is equal, but the pressure at the point of the spike is so great that we feel a sting because it penetrates deeper into the skin.  One of the consequences of the above is that we can get a very large pressure with a small force, reducing the area on which that force acts. We can also increase the area to produce a small pressure even though the force is great. For this reason, the blade of a knife acts with greater pressure when the knife is sharp, or a nail penetrates wood more easily with a sharp tip, or we use snowshoes or skis to move through snow without falling, or the floor suffers more if you walk on it in high heels than if you do it in slippers. The unit for pressure is the pascal (Pa) and by definition it is 1 N per 1 square meter. If we take a container with a bottom area of 1 m² we can pour so much water into it that its weight will be 1 N. Then the pressure on the bottom of that container will be exactly 1 Pa. How much water should be poured to achieve this and what will be the thickness of the layer of water when it evenly covers the entire bottom of the container?

One liter of water has a mass of 1 kg, that means a weight (mg) of 10 N. So, to have a weight of 1 N we need a ⅒ of a liter or one deciliter (0.1 ℓ) of water. After a deciliter of water is spread evenly over the bottom of our square meter, we will get a layer with a thickness of 0.1 mm. A layer of water of a tenth of a millimeter creates a pressure of 1 Pa! So small is Pascal. It seems that it is enough to wipe a surface with a wet cloth and you get a pressure of one Pascal. In meteorological reports rainfall 🔎 The liquid exerts pressure on the bottom of the vessel due to its weight mg, therefore the pressure on the bottom is the ratio of this weight and the bottom area S. In the further derivation, the area is shortened and we get expression that shows that the pressure at a certain point of the liquid does not depend on the geometry of the vessel except for the depth.

This pressure is called

hydrostatic pressure 🔎 p = ρ g h

However, this is not the only pressure to consider, as the vessel containing the liquid is normally exposed to the atmosphere, whose air mass also exerts pressure on the surface of the liquid, and thus the pressure. Therefore, the pressure at a point inside the liquid will be the sum of the hydrostatic pressure due to the column of liquid above that point, plus the external (atmospheric) pressure on the surface. This is the fundamental principle of hydrostatics: p = po + ρ g h.

Hydrostatic paradox 🔎PARADOX [gr. Παράδοξος = unexpected, strange] is an opinion, a judgment that differs from the usual, generally accepted, goes against (sometimes only at first glance) common sense; an unexpected phenomenon that does not correspond to the usual ideas in science. is the fact that the liquid pressure forces on the bottom of different containers filled to the same height with the same liquids are always the same regardless of the amount (volume, weight) of the liquid. Containers of the same height only differ in shape - a conical container can hold a smaller amount of liquid, and a container that expands upwards can hold a larger amount of liquid.

At first glance, we would expect that the pressure on the bottom of the middle container will be the lowest, and on the bottom of the right - the highest. This assumption is refuted by the experiment because the dynamometers show the same pressure force, which means the same hydrostatic pressure in all three vessels. We conclude: The pressure of the liquid on the bottom of the container does not depend on its shape! The difference between the weight of the liquid and the force of pressure on the bottom is caused by the reaction forces of the walls, so in a container that narrows upwards, these forces act on the liquid diagonally downwards (pressing the liquid to the bottom), while in a container that expands they act on the liquid diagonally upwards ( make the liquid lighter). The fact that the pressure in the liquid also acts upwards is shown by Gravisand's experiment which requires a really minimal equipment (a tube with a ground edge and a smooth plate a). We press the plate with our hand on the lower opening of the tube and hold it with a tied thread b. Then we immerse the tube in water. If we let go of the thread and stop holding the tile, it will remain pressed due to the pressure of the liquid c. To check, we pour colored water into the tube d and see to what level it should be poured in order to equalize the pressures and separate the tile e.

The physical meaning of this paradox is that the weight of the liquid in the container is different from the pressure force on the bottom (for the middle and right containers). The hydrostatic paradox can be clearly demonstrated by communicating vessels. These are containers interconnected by liquid passages and have a common bottom. In them, the surfaces of a homogeneous liquid at rest are at the same level, regardless of the shape and size of the individual container. Because the pressure on the vessel walls is equal at any horizontal level.

Liquids act by pressure both on the bottom and on the walls of the container. And that pressure depends on the depth, which can be easily demonstrated by the outflow of the jets from the holes on the vessel and by comparing their ranges on the ground, which should be sufficiently lower than the lowest opening of the vessel itself.

The water tower is a facility in the water supply network of lowland settlements. It is a tank raised high above the ground to store drinking or industrial water. With an elevated tank, not only a temporarily sufficient amount of water is achieved, but also sufficient and uniform pressure in the water supply network. Pressure oscillations on the inlet side (filling) and water consumption fluctuations on the outlet side (discharge) are compensated by the height and water supply. The result is a lower load on the filling pump and the creation of pressure in the supply network.

In addition to liquids, pressure also exists in others

fluids, as well as in air. The first proof of atmospheric pressure was performed by the Italian physicist Torricelli 🔎  If we include the values ρHg = 13600 kg/m³; g = 9,81 m/s²; h = 0,76 m in the expression for the pressure of the liquid column p = ρ g h we will get a value of 101325 Pa. It is the pressure of the column of mercury which, due to the balance with the air pressure, is also the atmospheric pressure. This proved that the atmospheric pressure can balance the mercury column pressure. If Torricelli had used water instead of mercury, the column that would balance the air pressure would have been 13.6 times higher (as many times the density of water is less than mercury), that is, it would have had a height of about 10.3 m.

A favorite experiment with the topic of air pressure consists of a glass beaker filled to the brim with water, which is covered with thin cardboard (eg. postcard) and then turned upside down. The question of whether the postcard will fall off or whether it will remain close to the opening of the glass will not instinctively always give a correct answer, even from physicists who are not familiar with the experiment. As we can easily show, the postcard remains adhered.

The usual explanation of the experiment is as follows „... that the pressure of the air acting from below is much higher than the pressure of the water column in the glass!“. We know that air pressure at sea level corresponds on average to the pressure of a column of water approximately 10 m high. Since the postcard is pressed against the glass by such a large external air pressure, it can easily hold a small column of water in the glass. If we try to perform the inverted glass experiment with ethyl alcohol instead of water, we will see that it fails and that the postcard will not be retained. This shows us in which direction to look for an answer. Namely, alcohol has several times less surface tension than water. Like water in a plumbing system, blood in the bloodstream is under pressure. In this way, it comes from large blood vessels and into the thinnest capillaries.

The heart acts like a pressure-suction pump, which rhythmically contracts and relaxes again. As a consequence of this way of working, blood is not pushed into the vessels continuously, but in spurts. That is why two values are always determined when measuring blood pressure: Upper - Systolic blood pressure Lower - Diastolic blood pressure Even today, blood pressure is expressed in units of mmHg - millimeters of mercury - since it was originally determined using a mercury column. One millimeter of mercury column equals 133 Pa. The first given value is always the systolic measured value (upper pressure), the second value describes the diastolic (lower) blood pressure. The optimal blood pressure value measured at rest is 120/80 mmHg. But slightly higher values are still considered normal. Only above 140/90 mmHg do doctors speak of elevated blood pressure, which is professionally called arterial hypertension 🔎With regard to the measured values of arterial pressure in the doctor's office, arterial pressure is classified as Both upper and lower blood pressure are constantly adjusting to the demands of our body. During physical exertion, the heart pushes more blood into the body, which increases the pressure. Blood pressure also increases with stress and excitement. By slower or faster heartbeats and narrowing or widening of blood vessels, blood pressure optimally adapts to different situations in our life. This regulation of blood pressure is vital for our body. Wind is the movement of air over the Earth's surface, caused by unequal heating of the Earth's surface, which leads to differences in the pressures of different areas. Wind strength can vary from a light breeze to hurricane force and is measured on the Beaufort wind scale. Wind pressure or wind power is an important quantity when calculating the effect of wind on an object, for example large surfaces, buildings or bridges. The dynamic pressure is the product of the aerodynamic coefficient c (depending on the shape of the object) and the wind stagnation pressure. The force is obtained by multiplying the pressure and the surface area of the object. Numerical simulation: Wind power, in some climates, can reach hurricane proportions and leave dramatic destructive effects. Such natural disasters can wipe out entire settlements from the face of the earth, especially in poor areas where houses are built mainly from cheap, light materials. At the time of the emergence of experimental science, in the 16th century, many scientists debated the question of whether there really is an empty space. Even the mayor of Magdeburg (and a physicist) Otto von Guericke 🔎 „Weil die Gelehrten nun schon

seit langem über das Leere, ob es vorhanden sei, ob nicht, oder was es sei, gar

heftig untereinander stritten (...) konnte ich mein brennendes Verlangen, die

Wahrheit dieses fragwürdigen Etwas zu ergründen, nicht mehr eindämmen

(...)"[1] „While scholars, for quite a long time now, have been vigorously arguing with each other about the void, whether it exists, or does not exist, or what it is at all (...) I could no longer hold back my burning desire to grasp the truth of that doubt to some extent (...)"

[1] Experimenta nova (ut vocantur)Magdeburgica De Vacuo Spatio The original hemispheres used in the Magdeburg experiment are kept in the Technical Museum in Munich. Model of Magdeburg spheres for school experiments in physics, their diameter is about 10 cm, so they can be disassembled with a force corresponding to a weight of about 75 kg. The hemispheres are pressed together with a seal at the joint. After the air is sucked out of them with a vacuum pump (the empty space in them is a relatively rough vacuum), the external pressure creates a force that prevents them from being disassembled. Guericke's spectacular vacuum experiments began in 1650 and made him a famous physicist and engineer. The culmination of his distinguished research series was an experiment on the effect of air pressure: the Magdeburg hemisphere. The demonstration of his famous experiment was performed for the first time in 1657 in the city of Magdeburg: For this purpose, Guericke used a vacuum pump to exhaust the air from two hollow copper hemispheres, which were sealed at the joint with a leather seal soaked in oil and wax, and had a diameter of 42 cm. The air acting on the hemispheres from the outside pressed the halves together. To show how much pressure the atmosphere causes, Guericke harnessed eight horses to each hemisphere, and they were unable to separate the hemispheres. What is the horse's pulling force?

Depending on the friction under the hooves, the horse can pull with a force always less than its own weight. The force of friction is generally the product of the pressure on the surface (i.e. the weight of the horse) and the coefficient of friction which depends on the surface (grass, asphalt, ice, gravel) and ranges between 0.2 and 0.4. So a 700 kg shod horse can pull with about 1500 N on dirt, but it cannot pull at all on ice.

Guericke wrote in his main work "Experimenta nova (ut vocantur) Magdeburgica De Vacuo Spatio": [1] translation: With his experiments, he disproved the then-prevailing belief about "Horror vacua" (lat. Fear, horror of emptiness), the so-called nature's fear of emptiness, which people at that time used to explain, among other things, the principle of pumping with suction pumps. Guericke showed that empty space really exists and how man can realize it. At the same time, it was clarified that air, like any other object, has weight. And according to this, the Magdeburg hemispheres are not "attracted to each other by the internal vacuum", but due to the high air pressure from the outside, they are pressed against each other. Calculation of the force required to separate the hemispheres

| |||||||||